Table of Contents

Come to Sarajevo.

Help me sow the seeds of compliance in the region.

This short email appeared in my inbox on December 22, 2015, at 8:20 a.m. It was from someone I had never met before, someone living more than 5,000 miles away from where I was sitting at that moment. That email was from Bojan Bajić—a compliance guy from Bosnia and Herzegovina, an eastern European country once part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Bojan wanted my help. He wanted to use compliance programs to fight corruption in the Sarajevo Canton—a sector of the country where he lived.

Bosnia and Herzegovina has a long history of corruption. Bribery, money laundering, and organized crime are commonplace. Political corruption exists at all levels of their government. People there lack civil and political rights. There’s a social stigma against reporting corruption too. Most believe it won’t do any good and, worse, they’ll suffer from life-threatening retaliation if they do report the wrongdoing they see. They’re right, not much happens when corruption is exposed. Most corruption cases are largely ignored by law enforcement and the courts. The country’s corruption is not just embedded in their government, law enforcement, and judicial systems; it’s also embedded in their businesses, many of which are still government-owned holdovers from the region’s communist days.[1] This post-communist, transitional country was trying to find its way in a freer world. Bojan was part of that change. What he was trying to do there was not just unusual, it was radical—and he wanted me to help.

“Sure,” I replied, and pressed send.

Few, if any, folks at the top of the compliance food chain would have said “yes” to traveling across the world and meeting someone they did not know, and some wouldn’t have even answered. Yet, when I read Bojan’s email, I thought: these are my people. I like to help the people nobody else seems interested in helping. I had no idea what was to come, but I’m glad I agreed to help. It turned out that my experience in the Sarajevo Canton was the most meaningful experience of my career.

Meeting Bojan and Višnja

After a 13-hour flight from Minneapolis, I arrived at the Sarajevo International Airport and watched my luggage come out on one of the two carousels. Everything there had seen better days. As I stood there, I have to admit I was a little concerned. What have you gotten yourself into, Roy? I hadn’t really checked into Bojan—I had no idea what kind of person he was. I would later be ashamed of this temporary moment of doubt.

I walked out of the baggage claim and there was Bojan and his colleague Višnja Marilović. They were very humble and reserved, and suggested I follow them to Bojan’s car. It was quiet in the car: neither said much. As we drove the streets of Sarajevo, I saw that many of the buildings were still full of bullet holes from the country’s civil war in the 1990s. While we began implementing the first compliance programs in the United States and thought it was tough, Bojan and Višnja were dodging bullets.

A meal out on my first trip to Bosnia and Herzegovina: (left to right) Rusmir Pobric, Mila Crnogorac Bajić, Višnja Marilović, Roy J. Snell, and Bojan Bajić.

(Photo courtesy of Bojan Bajić)

They took me to a restaurant for coffee, and then both started opening up. Bojan talked a little, but when Višnja began talking, I was moved like I had never been moved before in my compliance career. It was all a little too humbling to share, but essentially she told me, “I can’t believe you came here . . . to help us.” She came close to tears. I saw their sincerity and felt terrible for doubting them.

I discovered that Bojan is as charismatic, cool, funny, and smart as they come. His ability to influence others is enviable. Višnja’s integrity and passion for her country runs deeper than most people in the world. Later, Višnja told me her compliance story. She had been working in one of those government-owned companies, and the director was acting inappropriately and unethically. He was taking money and other things of value from the company, and Višnja was the accountant—she knew everything he was doing.

“I saw corruption, fraud, collusion, bribes, and how the company was collapsing together with all the employees and their families,” she later said.[2] She wrote to the director and told him that she knew what was happening, from tax evasion to money laundering. She confronted him in person too, but he refused to stop.

“I had a choice,” Višnja said, “to leave the company or stay and make things right. To stay and make things right—that was my choice.”[3]

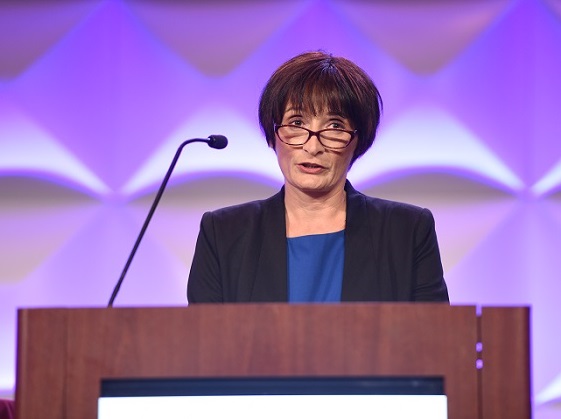

Višnja Marilović gave a powerful speech about corruption and her experience as a whistleblower without any protections while accepting SCCE’s International Compliance Award in 2017.

(Photo courtesy of the SCCE/HCCA archive)

She reported the director’s misconduct to the government, and as a result, she learned the true meaning of retaliation. She became isolated, discriminated against, and then was fired from the company. She was threatened to the point of needing police protection for her and her children. Soon after, she met Bojan, who was running an organization that advocated for whistleblowers. She told him all of what happened to her when she became a whistleblower and exposed the truth.

Bojan’s response was not forlorn, it was very hopeful. He told Višnja: “We will not cry. Let’s write a law. We need some law to protect [whistleblowers].”[4]

That’s just what they did. Then Bojan, Višnja, and their colleagues convinced eight parliamentarians to support their law.[5] It passed, becoming the first national whistleblower pre-court protection law in the country and all of Europe.[6] Over the next six years, they developed a whole compliance program based on the seven elements of compliance.[7] They used the SCCE website as the source of their compliance knowledge. “We read, analyzed, and discussed every word that we found there. We had a deep understanding of the purpose of rules and ethics in business,” Višnja said.[8]