It was probably around 1995, the midpoint of my career. I was managing close to 30 people who determined what doctors should charge for their services. CEO Marc Dettmann and I were walking down the hallway and he had a long document in his hand. It was written by someone in the enforcement community—probably a few someones. The document was a settlement between the enforcement community and a prominent organization. Of all the rambling pages of legalese, Marc had turned to one page and was pointing to one sentence.

“It says here that their organization has agreed to hire a compliance officer and implement a compliance program. Maybe we should do that before they come visit us?” he said. By “they,” Marc meant the enforcement community. I nodded and told Marc that it sounded like a good idea, but I really didn’t have a clue how brilliant his summary of this convoluted document was. He saw the enforcement train coming. Years later, this and several other insightful decisions Marc made saved our organization somewhere around $30 million.

“Why don’t you be our compliance officer?” Marc asked me.

I was still operating at about 30 leagues under his sea. I did not have a clue as to what he was asking me to do . . . no clue what a compliance and ethics officer was or how a compliance and ethics program functioned, but I was honored that he thought I could do more for him.

“I’d be glad to,” I told him.

That’s what I always said to anyone who ever asked me to do something new―“sure.” I had no plan for my career, but “sure” opened doors. Little did I know at the time, but that answer would change my life forever.

The Greatest Mentor: Marc Dettmann

Roy J. Snell, Aaron Gray, Andy North, and Marc Dettmann at a golf outing, mid-1990s

(Photo courtesy of the author)

In 1995, Marc Dettmann saw something very important that most of us could not see―the beginning of the compliance profession. This was not surprising, since Marc had a Harvard law degree and a Wharton MBA. More important to me, he was just a regular guy with mass quantities of common sense. And not just one kind of common sense; Marc had many different kinds of common sense. He dressed like a regular guy instead of a CEO, walked like a regular guy, and talked like a regular guy. Most people I had met before then couldn't see the forest for the trees. Marc could see through the forest, the trees, the leaves, and down to some microscopic organism of great importance to his organization. That day when he asked me to become a compliance officer, he had read through all the legal mumbo-jumbo and pulled out one sentence that would have a huge impact on his organization and ultimately, in my vivid imagination, on all industries and countries around the world. To Marc, it was just another day of trying to make sure he and his organization were successful. I owe a lot to Marc, the greatest mentor I would ever have.

Creating HCCA and SCCE

As a result of my accidental entry into compliance, my career would zig and then zag very randomly. I would learn a lot of different lessons, all of which I would eventually use when I finally got to create something. That “something” I and a couple other people created would become the largest professional associations for compliance and ethics professionals in the world―the Health Care Compliance Association (HCCA) and the Society of Corporate Compliance and Ethics (SCCE).

The Compliance Big Bang

When I became a compliance officer it was the beginning of what I like to call the “compliance big bang.” Many of us think we might have played a role in it. Although everyone I know who was there at the beginning describes it a little differently, the story goes something like this.

Essentially, the government (particularly those involved with the enforcement community) got tired of chasing down corporate wrongdoers. They wanted organizations to self-police. In the 1990s, a series of events would eventually, in my opinion, change organizations forever. Although I was entirely clueless that it was happening to me at the time, I was at the epicenter of this change.

It all began with settlements, like the one Marc read. This settlement may not have started the compliance movement, but it was surely an important part of the beginning. It really wasn’t an agreement in the traditional sense, where two people or organizations sat down and each party compromised on something. But rather, the settlement was a number of demands the enforcement community had imposed on the organization. They had to agree to these demands or things could get much worse. The organization received a clear message with that settlement: the government wanted them to self-police.

Here’s how it all started. About a year into my first compliance role, an employee of mine gave me Mary Dunaway’s business card and said I should call her―she was the corporate compliance officer for University Physician’s, Inc. I didn’t always listen to this somewhat difficult employee, but luckily I did this time and called Mary.

During our long conversation, I was particularly intrigued with Mary because I had never met another compliance officer. I can’t tell you how strange it was to have a new job at the age of 40 that I’d never heard of before. On top of that, I’d never met another person with the same job as me. Clueless doesn’t begin to describe my state of mind.

Now that we’d joined forces, I suggested to Mary that we hold a meeting in Minneapolis for compliance officers. We tacked it onto the Medical Group Management Association conference and then searched the internet for compliance officers to invite. We found a few, mostly those who had been hired after the government forced their companies to do so. As I recall, we invited 30 people . . . and 65 showed up. They came from across the country for what would be the first meeting designed for and run by compliance officers.

That day―October 13, 1996―was surreal. The room was full of people who spoke my language. Mary and I saw that there were more of us than we realized. During that three-and-a-half-hour meeting, we all learned so much about the role of a compliance officer and the function of a compliance program. At the end of the meeting, I got up, thanked everyone, and said, “We need to start a group.” Then Brent Saunders, the Thomas Jefferson University compliance officer, came up to me and said, “I need to be involved.” We went to dinner that night and started thinking about what kind of organization we could form. I wrote “Health Care Compliance Association” on one side of a napkin and then a short mission statement on the other side. What I would give for that napkin now. Our mission was simple: we wanted HCCA to be “a collaborative forum promoting integrity and ethical behavior through the development of comprehensive compliance programs throughout the entire health care industry.”[1]

I told Brent we needed Debbie Troklus; she seemed like someone who could help us start this new organization. I found her at the conference and she said, “Not interested. I am an interim compliance officer.” Luckily, I got her to agree to help anyway . . . and she went on to create the most significant set of credentials for compliance professionals in the history of our profession.

We were doing something completely new―something none of us really knew how to do, but we quickly figured it all out. We invited people we knew to serve on the board and then each took a part of operations, because we had no staff. Debbie made up a one-page membership brochure, started getting checks, and called me asking, “What do I do with this money?” I told her, “Open up a bank account.” Around 50 people became members that year, when we sent out our first newsletters, started a listserv, created a simple website, and organized our first educational programs as membership benefits.

One of HCCA’s first newsletters and its first membership brochure

(Images courtesy of the SCCE/HCCA archive)

Brent suggested I become the first president of HCCA . . . and I agreed. Our first real office space was a room with a desk, computer, and phone, donated to us by Marc at the organization where I was working as a compliance officer. We hired a temp as our first employee―Henry Youmans, who stayed with us for the next few years. And we held HCCA’s first annual conference in Los Angeles in November 1997. We called it the National Health Care Fraud and Abuse Symposium. We had 24 speakers and 152 attendees.

After two years as president, I passed the baton to Brent: HCCA’s second president. Things were growing so fast . . . it was a bit frightening, actually. By 2000, a few of our board members became concerned that the president’s role was consuming too much time, as the organization was getting bigger and more complicated. So, the board decided to hire a CEO. They sent the president at that time―Greg Warner, the compliance officer of the Mayo Clinic―to come see if I wanted the job. We worked everything out and I became CEO in February 2001. Just three years later, we started the SCCE. As of early 2019, HCCA and SCCE hold more than 100 conferences each year all over the world. And the two associations now have more than 20,000 combined members. Who knew?

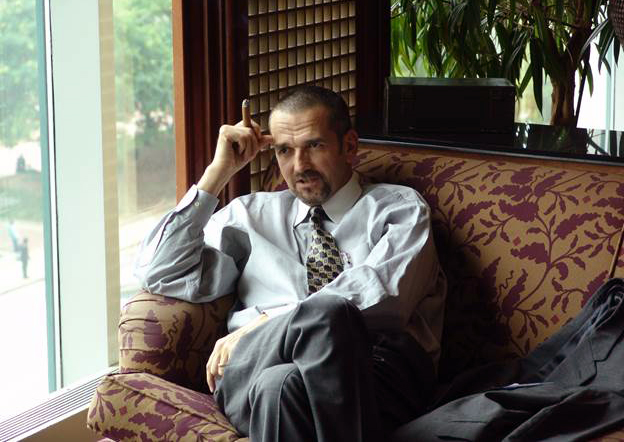

From early on, I found that sitting in between sessions and talking with conference attendees was one of the best ways to understand what was going on in the compliance industry.

(Photo courtesy of the SCCE/HCCA archive)

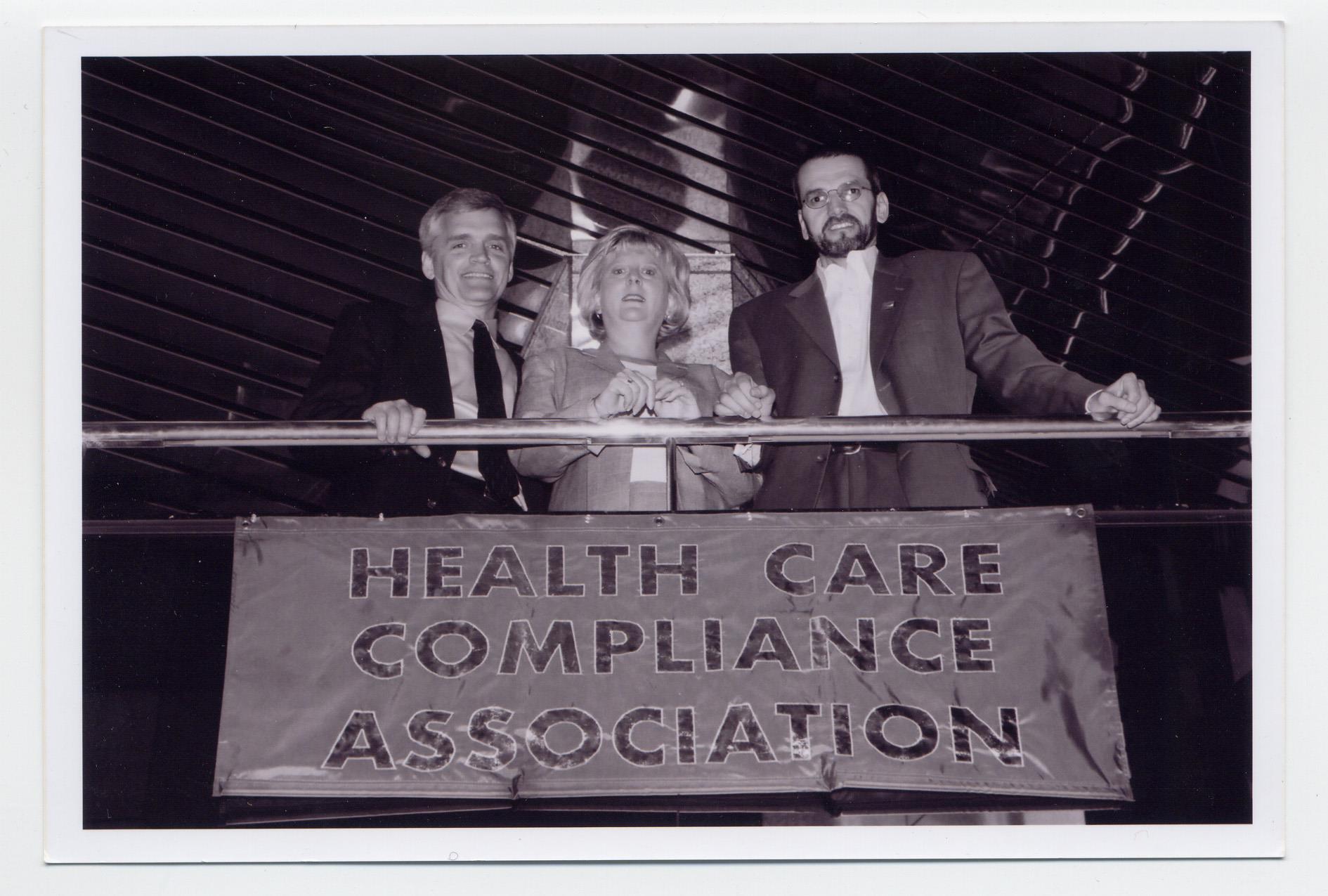

Greg Warner, Debbie Troklus, and Roy J. Snell, at one of HCCA's first annual conferences

(Photo courtesy of the SCCE/HCCA archive)