M.A. Hall (mhall@dugganbertsch.com) is the Healthcare Practice Co-Lead at Duggan Bertsch LLC in Chicago.

Erika Stevens (erika@recherchetransformationrapide.com) is a Principal at Recherche Transformation Rapide in Lumberton, NJ.

Mary Veazie (mlveazie@mdanderson.org) is the Executive Director of Clinical Research Finance at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

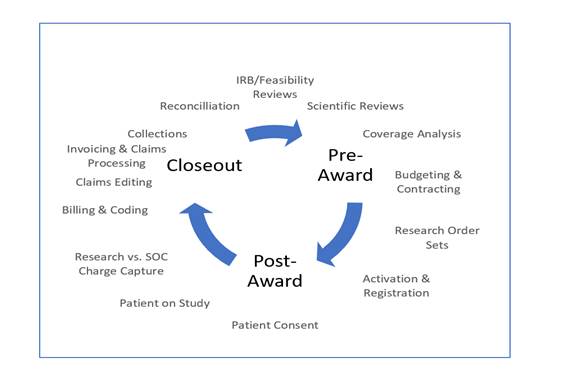

The field of clinical research is no different than any other in the healthcare industry, in that there are federal and state regulations and laws that affect its revenue cycle. Institutions conducting research on humans must comply with all applicable laws and regulations throughout the clinical research cycle in order to continue to provide care for patients, bill for services, and maintain funding. Regulatory requirements and laws impact each phase of the clinical research revenue cycle (CRRC):

-

Institutional review board (IRB)

-

Pre-award, study start-up

-

Post-award

-

Close-out

For this article, we will discuss the compliance risks associated with the regulatory requirements within the pre-award, post-award, and close-out phases of the CRRC and how noncompliance with regulatory requirements across the revenue cycle can affect a clinical research department’s fiscal bottom line. In FY 2017, the federal government recovered $2.4 billion from healthcare fraud actions, which is a return on investment of $6.10 for each dollar spent.[1] For clinical research, understanding compliance risks is essential for everyone, including executive management (C-suite), to avoid significant penalties from federal and state governments. We will discuss and identify the benefits of introducing the concept of proactive compliance to a CRRC program as the most advantageous way of addressing regulatory matters for an institution.

Proactive compliance

Proactive compliance is the system of determining and incorporating the principles of compliance to every process of development or redesign for a CRRC program. New policies, processes, and technologies are only introduced into the revenue cycle of a clinical research program when there is an analysis of the compliance implications. Additionally, to confirm proactive compliance principles were followed by all involved in the CRRC program, there are methods of oversight that allow follow-up to ensure that the concept is recognized and accepted for each CRRC phase that involved regulation. The healthcare fraud laws that apply to the traditional care model are applicable to clinical research, including the False Claims Act (FCA),[2] the Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS),[3] and Stark Law (42 U.S.C. § 1395nn).

Additionally, anti-fraud principles under the FCA that transfer to clinical research include medical necessity, billing for services provided, and unbundling of charges.

These principles put a clinical research program at risk if the financial and study teams running a program are not aware of them or fail to realize the appropriate application. A clinical research department that adopts the proactive compliance approach in the pre-award, post-award, and close-out phases of the CRRC can expect that regulatory concepts that dictate day-to-day operations are considered. This leads to timely identification of risks and results in prioritization throughout the life cycle of a clinical trial or study through the development of controls and other mechanisms.

In addition to the specific liabilities discussed below, a finding of liability against an entity or individual under the AKS, the FCA, or Stark Law can lead to the exclusion from participating as an entity or provider of any services or items reimbursable by federal healthcare programs for periods that can range from three years to permanently. This includes clinical research programs that bill or receive funds from the federal government. Primary authority for the administration, audits of compliance, and enforcement of the federal anti-fraud laws rests with the Office of Inspector General (OIG) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. For criminal prosecutions (when permitted) upon referral by the OIG, the U.S. Department of Justice has primary authority.

Anti-Kickback Statute

The AKS prohibits the exchange of anything of value―cash or “in-kind”―to induce referrals for services or items payable by a federal health program, and the AKS carries penalties of up to $25,000 or imprisonment of not less than 5 years. Under the AKS, the substance of conduct in operating a clinical research program will trump form, that is, the formal language of agreements entered into for purposes of establishing the liability of a party. Targets of enforcement actions, in the cases of entities involved in prohibited conduct, will include the individuals in control of the entities and facility employees.

False Claims Act

The FCA is a civil liability statute that makes it illegal for any person to knowingly make a false record or file a false claim for reimbursement to any federal healthcare program. The primary civil remedies for a violation of the FCA are: (1) imposition of substantial civil monetary penalties, ranging from approximately $10,000 to $21,000 per false claim (meaning per unit of service or item sold for which reimbursement was sought), plus (2) treble damages on the aggregate amount originally paid by the government on the false claim. Under the FCA, the mere filing of a claim for services, the submission of a prescription, or certification of a medical device can be deemed the filing of a false claim in violation of the statute.

Stark Law

The Stark Law (aka the physician self-referral law) prohibits physicians from referring patients for receipt of a whole range of services, commonly referred to as designated health services, if they are to be payable by federal healthcare programs and rendered by entities with which the prescribing physician or members of their immediate family have a direct or indirect financial interest.

The Stark Law is a strict liability statute, that is, specific intent to violate the law is not required for liability to attach, because the violation occurs by the mere referral to an entity where a financial interest is held. Financial interests prohibited by Stark include ownership and investment interests in entities, as well as compensation arrangements involving unaffiliated entities. Additionally, under Stark a physician is prohibited from presenting or causing to be presented claims to a federal healthcare program (or billing another individual, entity, or third-party payer) for the referred services.

Penalties for Stark Law violations include fines up to $15,000 for each billed service, plus three times the amount of the claim overpaid and the possibility of exclusion from participation in federal healthcare programs. Like the AKS, Stark does provide for exemptions (i.e., safe harbors) that permit the holding of such financial interests if structured in accordance with existing regulations.

Each of the regulations and anti-fraud principles detailed here apply to clinical research programs. If an institution is not performing proactively throughout the revenue cycle, it can find itself running afoul of the applicable compliance laws and, thus, having to report incorrect billing and/or return funds along with the associated penalties.

The clinical research revenue cycle

CRRC identifies the activities related to clinical research that affect financial outcomes. Specifically, the revenue cycle captures details for identifying opportunities for revenue, pitfalls for losses, and risks associated with issues of noncompliance in meeting research finance regulatory requirements.[4]

The ability to capture clinical procedures related to research mitigates CRRC compliance risks. Understanding the complexities of compliance risks associated with clinical research is complicated for many organizations, because the potential pitfalls exist throughout the cycle. Financial errors occur in the budgeting, patient identification, charge capture, billing, accounts receivable, and reconciliation processes. Establishing clearly defined processes for review of study-related and non–study-related charges prior to study initiation thwarts future billing issues. Assessing financial feasibility and implementing risk tolerance steps can reduce compliance findings.

In assessing risks, identifying the potential areas of financial/compliance risk throughout the CRRC will enable better safeguards (see Figure 1). For example, in the pre-award phase of the CRRC, many institutions lack a formal clinical research financial budget process, which places the institution at risk of not capturing and recouping all research costs. Further, without a documented coverage analysis, institutions are at risk of potentially billing Medicare for non-qualifying clinical trials and/or potentially inaccurate clinical research billing. In addition, this step is key to the successful execution of the remaining steps in the billing compliance continuum. Institutions may also be losing revenue due to billing denials by a third party for services billable to a sponsor.

During the post-award phase, patient tracking/enrollment registration risks arise without a centralized location for recording all enrolled clinical research participants. Without a central repository, registration and scheduling of these participants is difficult and could lead to errors.

The coding and billing of clinical research activities is complex, and risk occurs without appropriate routing of standard of care vs. research-specific charges. Institutions are at risk for improper billing, loss of revenue due to payment denials, and noncompliance with Medicare clinical research coding and billing regulations.

Another operational risk develops due to inconsistent invoicing and tracking processes that may result in unbilled invoices and loss of potential revenue, such as those related to a clinical trial sponsor. In the absence of established processes and controls, these steps are often overlooked.

Finally, reconciliation risks occur without a periodic reconciliation process, such as loss of revenue and not remediating improper billing in a timely manner.