Dan Brady (daniel.brady3@usbank.com)is Assistant Vice President in the Global Ethics Office for U.S. Bancorp in Minneapolis, MN.

Business ethics is typically perceived as the domain of lawyers, academics, accountants, or perhaps highly paid consultants. All of these fields (and others) play a role in defining and developing a strong ethical culture. But what about science? Particularly applied science, which leverages existing knowledge to solve problems. Ethics is inextricably linked to social and behavioral sciences; however, we often view that as background — a way to understand why people act the way they do or make unethical decisions. I suggest a new approach for implementing an ethics program and reinforcing an ethical culture. The approach derives from public health, an applied science that has proven highly effective in responding to some of the most serious challenges facing society (e.g., promoting vaccinations, smoking cessation, reducing pollution).[1]

A seemingly unusual application, public health and business ethics have a common thread. Many interventions in public health are taken up with the goal of persuading a population to refrain from some undesirable behavior (e.g., smoking, speeding, eating junk food) or, conversely, to engage in a desirable behavior (e.g., wearing seat belts, exercising, getting immunized). So it is with ethics, too. It’s true that certain practices leading to negative outcomes, such as smoking on airplanes or refusing to wear a seat belt, have been restricted by law. But much unethical behavior is also illegal, yet people still do it. As business ethics practitioners, our goal is to persuade a population (our company) to refrain from unethical behavior while simultaneously promoting ethical behavior. The parallel continues, because many primary public health interventions are focused on awareness, communication, and training, as are many efforts to reinforce ethics. Although there is no single, uniform approach to creating an ethical culture, there are models that can be instructive for this purpose.

Model behavior

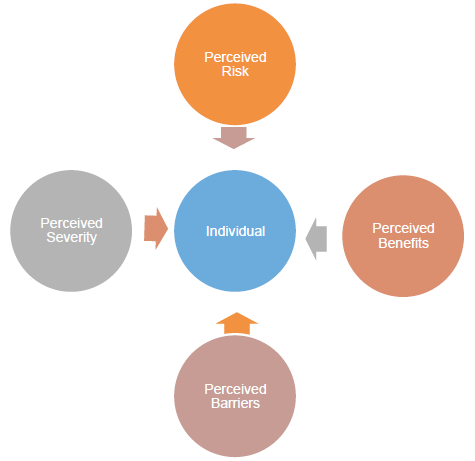

Two common public health models[2] apply to ethics: the health-belief model and the social-ecological model. The health-belief model (see figure 1) captures the more common approach to business ethics programs. In this model, an individual receives information about the choices before them and examines the weight of evidence to determine if the risks outweigh the perceived benefits of a particular choice. In public health, this means providing people with a picture of the negative aspect of a health behavior while encouraging or even empowering them to refrain. There may not be a framework for eliminating that behavior, rather the individual is responsible for making the right (most economical) choice. For example, consider a residential recycling program that encourages people to use the infrastructure (bins that are picked up) available to them.

In a fledgling ethics program, we see this model applied similarly. Employees are told which behaviors are unacceptable — along with a little bit about why they are — and encouraged to report issues or seek guidance. They may be told repeatedly and directed by managers to act ethically, but they are not told how or what that means to their company. For some organizations, that’s the extent of awareness. Consider an annual PowerPoint presentation that serves as training on appropriate use of company assets as an illustration of this approach.

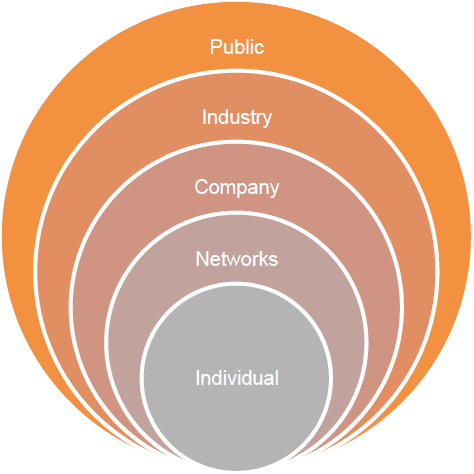

In contrast, the social-ecological model (see figure 2) takes a distributive, systems approach by engaging the entire population in addition to the individual. It establishes a view of an issue that assumes an individual’s behavior is influenced at multiple levels, and in turn, the individual may influence those same levels. Emphasizing five separate spheres that influence an individual’s actions, the social-ecological model helps practitioners identify where (which sphere) to apply targeted interventions. In a public health scenario, this may mean enlisting advocacy groups along with advertisers and policy makers. This is the case for the residential recycling example, which may be promoted by environmental groups, adopted by neighbors, and advertised by a municipality or collector.

In a business ethics situation, it translates to outreach to business networks, inclusion in company-wide initiatives, and benchmarking with industry associations. We do this while continuing to deliverinformation and evidence at the individual level. By taking the segmented approach prescribed by this model, it is more likely that employees will hear our message and act accordingly.