By Susan Fenimore Dworak and Cristina Jerney[1]

ID Checking Regulations

Most jurisdictions have no set standard for checking ID, making legal compliance complex and confusing. It does not have to be this way. Well-thought-out and carefully drafted compliance plans can serve to protect businesses, workers, and communities from a number of dangers and also ensure workers have the information needed to make informed choices when it comes to confirming identity. We must collectively adopt and enforce policies that support a new industry standard and legal standard for checking ID and confirming identity.

Government agencies regulate products and services across many industries to protect people. Access to those products and services requires confirmation of age or identity. Millions of workers are required to check IDs as a daily part of their job duties, but many, if not most, have never been properly trained to check IDs to confirm identity. For example, when it comes to the sale and service of alcohol in the US, those who do seek training typically attend a 2- to 4-hour responsible beverage service class, and during that time hear an average of 10 short minutes on ID checking. Given the risks caused by fake IDs, that is unacceptable.

There are hundreds of versions of real IDs in circulation in the US, and there are large numbers (millions, in fact) of sophisticated fake IDs on the market. Those fake IDs are built to fool devices like ID scanners, leaving the ID-checking process up to the humans who have not been adequately trained. Properly checking IDs is effective, but current solutions are inadequate. This makes compliance with checking ID and confirming identity very difficult.

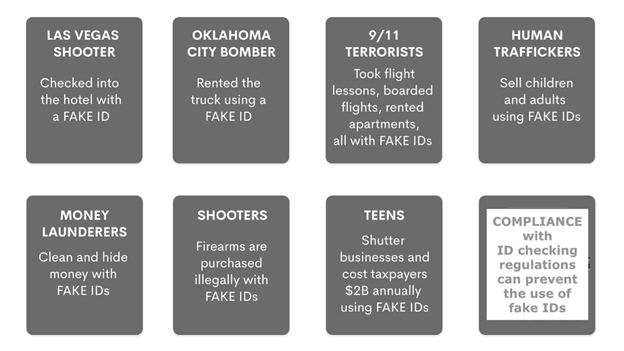

The cost of noncompliance is high, and there are large, costly, and increasing problems with fake IDs. One fake ID used once can cause massive legal and financial damage to businesses and government agencies and also untold heartache for society. According to law enforcement, the Las Vegas shooter reportedly checked into the hotel with a fake ID, the Oklahoma City bomber rented a truck with a fake ID, and the 9/11 terrorists used a series of fake IDs to carry out their acts (the federal government responded in part by enacting the Real ID Act).[2] Fake IDs are also used in human trafficking, trading exotic animals, financial fraud, identity theft, and countless other crimes. As fake IDs become more sophisticated, they not only threaten businesses and people who check IDs, but also communities and society as a whole.

Fake IDs cause deep and swift damage across nearly every industry. Compliance with ID checking regulations can prevent legal, financial, and social consequences.

The answer to mitigating risk in person-to-person transactions is mandating specific ID training for frontline gatekeepers. These gatekeepers are critical to the ID checking process because they cannot only see and feel security features on government-issued IDs, but they can observe and assess behavioral nuances often associated with the use of a fake ID. They also have the innate ability to conduct human facial recognition to confirm identity, matching the person presenting the ID to the photo on the ID. These are tasks no device can collectively perform.

Understanding Real and Fake IDs

To understand the importance of mandating training, it’s important to understand IDs. To understand fake IDs, it helps to first understand real IDs. In the US, there are 59 jurisdictions that issue government driver’s licenses and ID cards: 50 states, one district (Washington, DC), five US territories, and three freely associated states. At any given time, each jurisdiction has a number of valid ID versions—and variations of those versions—in circulation, resulting in hundreds of currently valid IDs in the US. These versions are updated periodically, and new versions are released over time, making it impossible to memorize every ID.

All of those IDs contain three kinds of security features: overt, covert, and forensic. Overt features can be easily seen with the eyes and felt with the hands. Covert features can be revealed with a simple tool, such as a flashlight, UV light, or magnifier. Forensic features require special equipment—typically available to law enforcement or government—with the exception of simple machine readable technology, such as barcodes and magnetic stripes, both of which can be read by simple scanners or scanning apps because they are both half a century old and easily forged.

The American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA) creates standards for the design of driver’s licenses and ID cards to improve the security of the cards and the “interoperability among cards issued by all North American jurisdictions.”[3] States spend millions of dollars on complex security features to make it more difficult to counterfeit IDs, including visual and tactile features meant for inspection by sight and touch. If gatekeepers fail to use visual perception and manual dexterity to confirm these features, the expertise of the AAMVA and the expenditure by Departments of Motor Vehicles are squandered.

The problem is that many (in fact, most) gatekeepers don’t know what security features to look for and feel on IDs and, as noted, it is impossible to memorize hundreds of IDs with extreme variations in overt, covert, and forensic security features. When people are trained to properly and thoroughly check IDs and are given access to current ID images, they can tell the difference between real and forged security features. The human senses, and specifically sight and touch, are the best defense in detecting fake IDs in person-to-person transactions.